More than a billion people eat fewer than 1,900 calories per day. The majority of them work in agriculture, about 60 percent are women or girls, and most are in rural Africa and Asia. Ending their hunger is one of the few unimpeachably noble tasks left to humanity, and we live in a rare time when there is the knowledge and political will to do so. The question is, how? Conventional wisdom suggests that if people are hungry, there must be a shortage of food, and all we need do is figure out how to grow more.

[...]

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, with an endowment of more than $30 billion, has embarked on a multibillion-dollar effort to transform African agriculture. It helped to set up the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) in 2006, and since then has spent $1.3 billion on agricultural development grants, largely in Africa. With such resources, solving African hunger could be Gates's greatest legacy.

But there's a problem: the conventional wisdom is wrong. Food output per person is as high as it has ever been, suggesting that hunger isn't a problem of production so much as one of distribution.

The Gates Foundation is focusing on technology, spending about a third of the $1.3 billion on promoting and developing seed biotechnologies, one of the largest recipients of which is everybody's favourite corporation, Monsanto.

However, all is not lost...

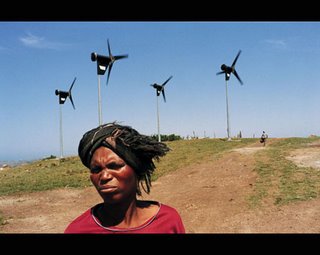

Despite institutional neglect, ecological farming systems have been sprouting up across the African continent for decades--systems based on farmers' knowledge, which not only raise yields but reduce costs, are diverse and use less water and fewer chemicals. Fifteen years ago, researchers and farmers in Kenya began developing a method for beating striga, a parasitic weed that causes significant crop loss for African farmers. The system they developed, the "push-pull system," also builds soil fertility, provides animal fodder and resists another major African pest, the stemborer. Under the system, predators are "pushed" away from corn because it is planted alongside insect-repellent crops, while they are "pulled" toward crops like Napier grass, which exudes a gum that traps and kills pests and is also an important fodder crop for livestock. Push-pull has spread to more than 10,000 households in East Africa by means of town meetings, national radio broadcasts and farmer field schools. It's a farming system that's much more robust, cheaper, less environmentally harmful, locally developed, locally owned and one among dozens of promising agroecological alternatives on the ground in Africa today.

Read the whole article from The Nation

Previously blogged about here